API Reference¶

Messages¶

Most data processing workflows have the same basic architecture and only differ in the type of data and how those inputs are formatted. Minor differences in this formatting can make almost identical code non-reusable. To address this issue, this framework insists on using a single data structure to pass information between components - the Message object. A Message consists of two components: a Pandas DataFrame and a TensorMessage. The former is a very general purpose structure that benefits from all of the features of the popular Pandas library - a DataFrame is essentially a dictionary of arrays. However, in the context of pytorch deep learning, we cannot use DataFrames for everything because we cannot store tensor objects inside a dataframe (Pandas breaks down tensors into unit sized tensors and stores those units as objects as opposed to storing them as one entity). The TensorMessage emulates the structure and methods of DataFrames, except it only stores pytorch tensors (in the future, tensor’s in other frameworks could be supported). Because of this, it also attempts to autoconvert inputs to tensors. With this combined structure, one could store metadata in the dataframe and example/label pairs in the TensorMessage.

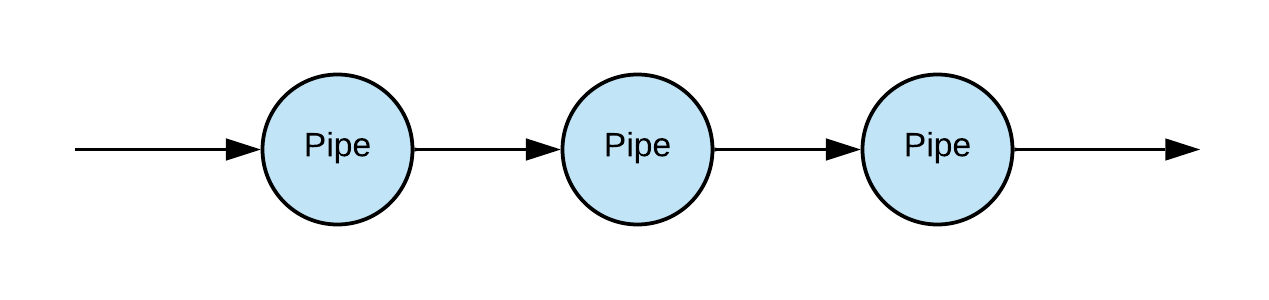

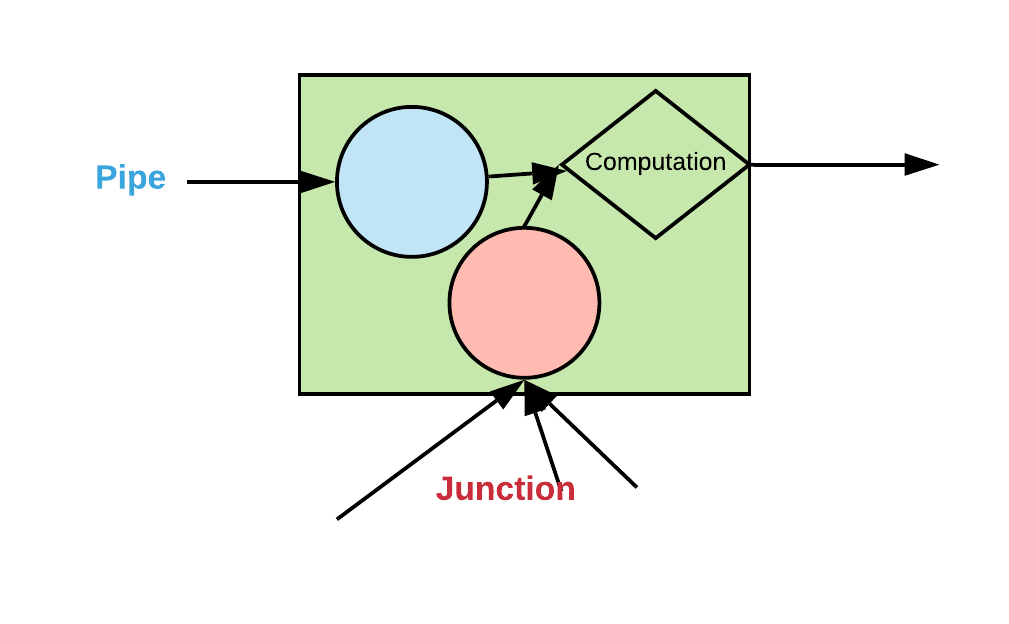

Pipes¶

With a uniform data structure for information transfer established, we can create functions and classes that are reusable because of the standardized I/O expectations. A Pipe object represents some transformation that is applied to data as it flows through a pipeline. For example, a pipeline could begin with a source that reads from the database, followed by one that cache those reads in memory, then one that applies embedding transformations to create tensors, and so on.

These transformations are represented as classes rather than functions because we sometimes want to be able to apply transformations in a just-in-time or ahead-of-time manner, or have the transformations be dependent on some upstream or downstream aspect of the pipeline. For example, the Pipe that creates minibatches for training can convert its inputs to tensors and move them to GPU as a minibatch is created, using the tensor-conversion method implemented by an upstream Pipe. Or a Pipe that caches its inputs can prefetch objects to improve overall performance, and so on.

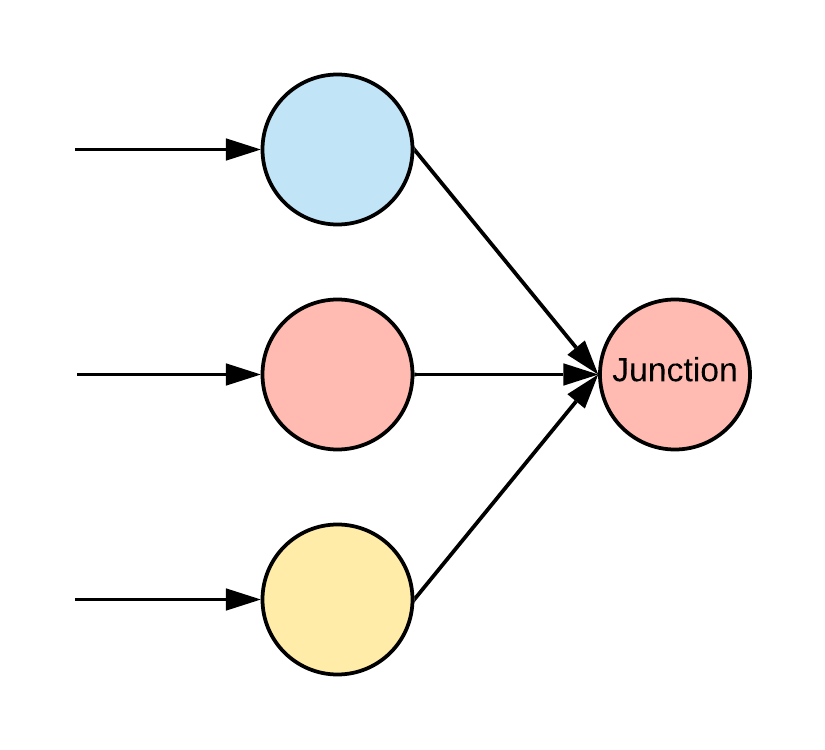

Junctions¶

Whereas Pipes are designed to have one input, Junctions can have multiple inputs, called components. Since there is no unambiguous way to define how recursive method calls would work in this situation, it is the responsibility of each Junction to have built-in logic for how to aggregate its components in order to respond to method calls from downstream sources. This provides a way to construct more complex computation graphs.

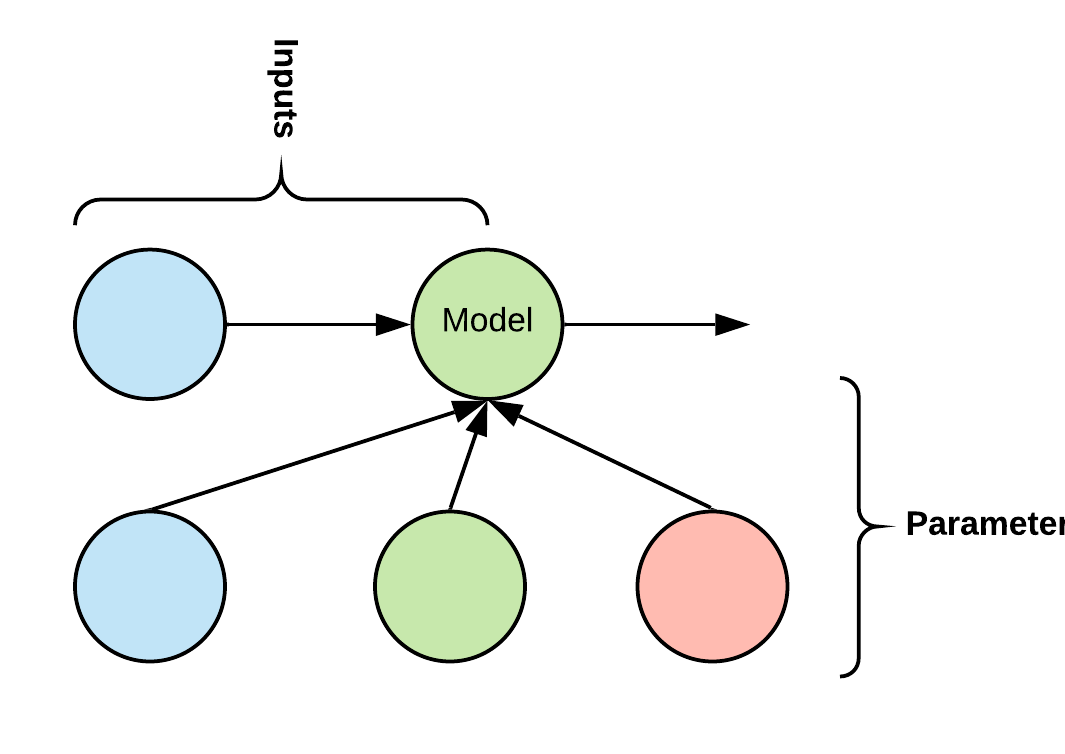

Models¶

Models are a data structure for representing mathematical models that can be stacked together, incorporated into pipelines, and have their parameters trained using PyTorch. These Models don’t have to be neural networks or even machine learning models; they can represent any function that you want. The goal of the Models class is to decouple the parameterization of a model from its computation. By doing this, those parameters can be swapped in and out as needed, while the computation logic is contained in the code itself. This structure makes it easy to save and load models. For example, if a Model computes y = m*x+b, the parameters m and b can be provided during initialization, they can be learned using gradient descent, or loaded in from a database.

Models function like Junctions with respect to their parameters, which are called components. These components can be PyTorch Parameters, PyTorch Modules, or some other object that has whatever methods/attributes the Model requires. Models function like Pipes with respect to their arguments. Hence, you can insert a Model inside a Pipeline. Models also function like PyTorch Modules with respect to computation and training. Hence, once you have created a Model, you can train it using a method like gradient descent. PyTorch will keep track of gradients and Parameters inside your Models automatically. You can also freeze and unfreeze components of a Model using the freeze/unfreeze methods.

m = LinearModel(components={'m': [1.]}) # Initialize model for y = m*x+b with m = 1.

print(m.required_components) # This will return ['m', 'b']. A model can optionally have initialization logic for components not provided

# For example, the y-intercept b can have a default initialization if not provided here.

print(m.components) # This should return a dict containing both m and b. The model should have initialized a y-intercept and automatically added that to it's components dict.

f = NonlinearModel(input=m) # Initialize a model that represents some nonlinearity and give it m as an input.

result = f(x) # Evaluates f(m(x)) on argument message x. Because m is an input of f, m will be called first and pipe its output to f.

State¶

Database¶

This module contains methods and classes for ingesting and reading data to/from a database. A user can specify a schema and stream messages from a source into a relational database. You can also create a source that streams data from a database based on a query. Because this module is built using SQLalchemy, it inherits all of the capabilities of that library, such as the ability to interface with many different relational databases and very precise control over schema and access. There are two sources: A TableSource implements methods for writing a Message to a table, and a DBSource is an iterable that produces Messages as it loops through a database query.

TableSource

A TableSource is initialized with an SQLalchemy table, and SQLalchemy engine, and an optional list of columns that the TableSource will write to in the table. By specifying columns, you can choose to use only a subset of the columns in a table (for example, if there are auto-incrementing ID columns that don’t need to explicitly written). In addition to methods for standard relational database actions such as rollback, commit, etc., the TableSource has an insert method that takes a Message object, converts it into a format that can be written to the database and then performs the insert. It also has a query method that takes the same arguments that the query function in SQLalchemy takes (or does a SELECT * query by default) and returns a DBSource object corresponding to that query.

DBSource

This Source is initialized with an SQLalchemy query and iterates through the results of that query. It converts the outputs to Messages as it does so, enabling one to easily incorporate database queries into a Source pipeline.

Experiment¶

The Experiment module offers a way to save data from individual runs of a model. This makes it convenient to compare results from different experiments and to replicate those experiments.

exp = Experiment('name', 'db_path', 'description')

will create a folder named db_path/name containing a sqlite file called name.sqlite. You can now save any objects to that folder using

with exp.open('filename') as f:

f.save(...)

This will create a file handle f to the desired filename in the folder. You can also use exp.get_engine(‘name’) or exp.get_session(‘name’) to get an SQLalchemy session/engine object with the given name that you can then use to save/load data. Combined with Fireworks.db, you can save any data in Message format relatively easily.

Factory¶

The Factory module contains a class with the same name that performs hyperparameter optimization by repeatedly spawning independent instances of a model, training and evaluating them, and recording their parameters. The design of this module is based off of a ‘blackboard architecture’ in software engineering, in which multiple independent processes can read and write from a shared pool of information, the blackboard. In this case, the shared pool of information is the hyperparameters and their corresponding evaluation metrics. The factory class is able to use that information to choose new hyperparameters (based on a user supplied search algorithm) and repeat this process until a trigger to stop is raised.

- A factory class takes four arguments:

- Trainer - A function that takes a dictionary of hyperparameters, trains a model and returns the trained model

- Metrics_dict - A dictionary of objects that compute metrics during model training or evaluation.

- Generator - A function that takes the computed metrics and parameters up to this point as arguments and generates a new set of metrics to

use for training. The generator represents the search strategy that you are using. - Eval_dataloader - A dataloader (an iterable that produces minibatches as Message objects) that represents the evaluation dataset.

After instantiated with these arguments and calling the run method, the factory will use its generator to generate hyperparameters, train models using those hyperparameters, and compute metrics by evaluating those models against the eval_dataloader. This will loop until something raises a StopHyperparameterOptimization flag.

Different subclasses of Factory have different means for storing metrics and parameters. The LocalMemoryFactory stores them in memory as the name implies. The SQLFactory stores them in a relational database table. Because of this, SQLFactory takes three additional initialization arguments:

- Params_table - An SQLalchemy table specifying the schema for storing parameters.

- Metrics_table - An SQLalchemy table specifying the schema for storing metrics.

- Engine - An SQLalchemy engine, representing the database connection.

Additionally, to reduce memory and network bandwidth usage, the SQLFactory table caches information in local memory while regularly syncing with the database.

Currently, all of these steps take place on a single thread, but in the future we will be able to automatically parallelize and distribute them.