Tutorial¶

The code snippets in this tutorial are meant to provide a demonstration of the core functionality and tools provided by the Fireworks library. If you have trouble running any of these snippets or understanding any of the text, feel free to ask a question on Github or reach out to me (smk508) directly.

Messages¶

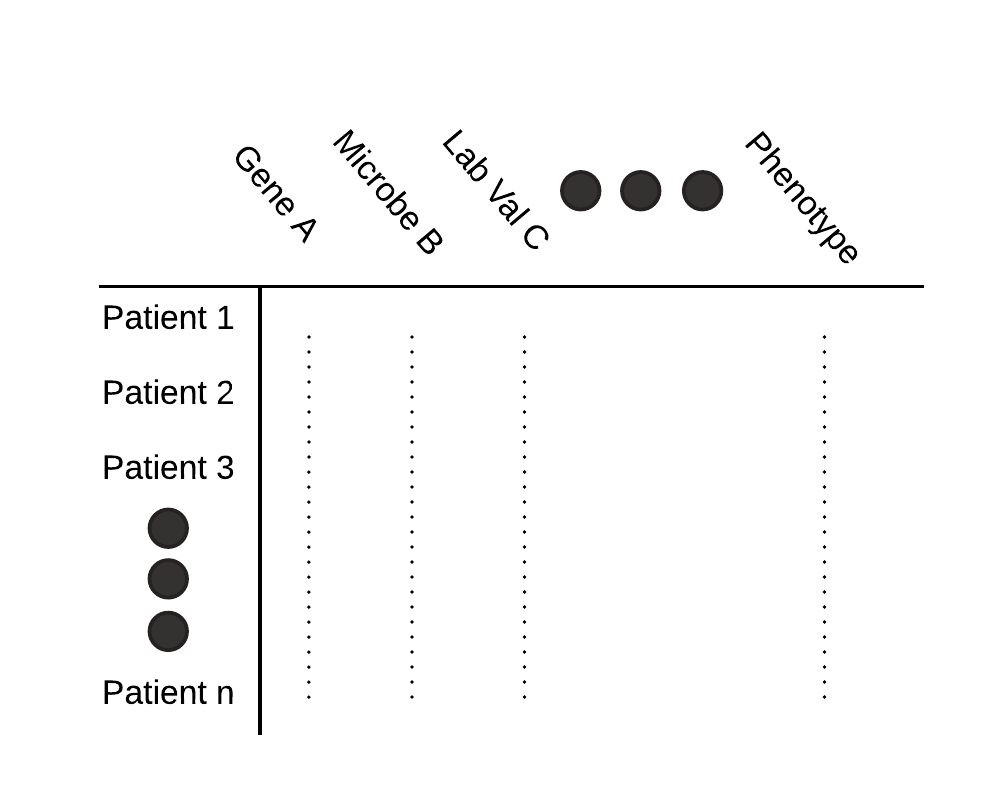

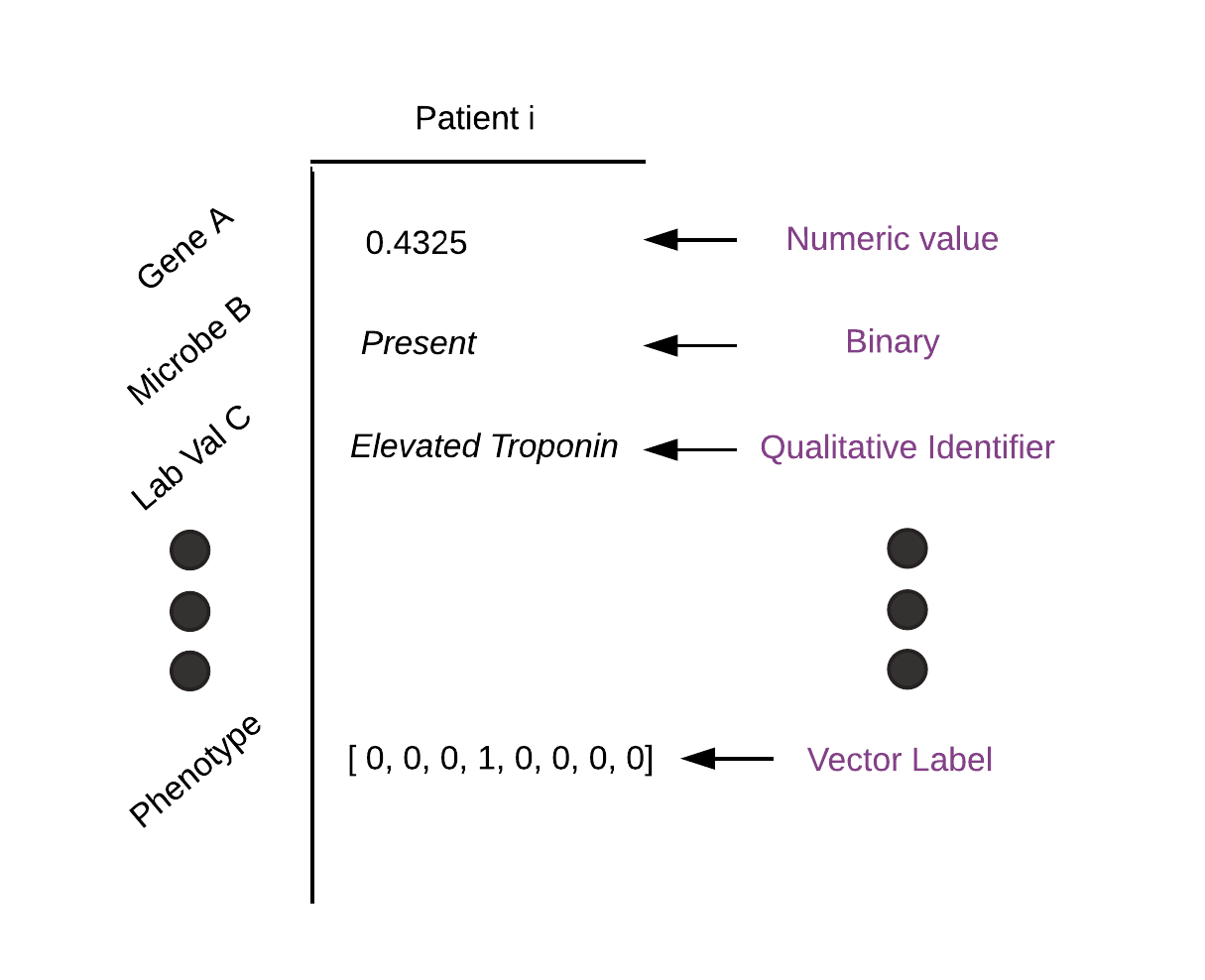

Tabular data formats show up everywhere in data analysis software and languages. SQL, Stata, Excel, R DataFrames, Python Pandas, etc. all represent data as using variations of the concept of a table. This is a matrix where the columns are named and the rows are indexed by number, data, time, etc. Working with data in this format is convenient because you can easily keep track of what each column represents, and the format is generic enough to support pretty much any task.

It can be tricky to use DataFrames with machine learning tasks, however, because you often have data of many different types, as in the example below. In particular, to make this work, you would need the ability to have columns containing the tensor-like objects that are used by deep learning frameworks to represent data.

Fireworks aims to solve this issue and make it easy to use DataFrames with batch processing and machine learning workloads, and specifically PyTorch. In particular, it provides an implementation of DataFrames called Message that can contain torch.Tensor objects. It also provides a set of primitives for performing and composing batch processing tasks using this data structure, and this is aimed to make it easier to perform preprocessing tasks, which is often a pain point when doing machine learning on large datasets.

For the most part, you can use Messages like Pandas DataFrames. That is, you can call Fireworks.Message() instead of pd.DataFrame(). There are a few key differences. First, Messages don’t have a way to adjust their index. In Pandas, you can choose how the rows of a DataFrame are indexed. For example, the rows could refer to timestamps or dates. Here, the only way to index rows is by number (ie. the nth row is accessed by calling message[n]). This simplifies usage when feeding data to a statistical model which only cares about getting the next batch of data.

Secondly, Messages can have torch.Tensor objects inside them. You can set a column of a Message to a torch.Tensor, and operations like append and indexing will work as you expect.

a = torch.random(2,3) message = Message({'x': a}) print(a) >> Message with >> Tensors: >> TensorMessage: {'x': tensor([[ 0.3087, 0.9619, 0.5176], >> [ 0.2747, 0.6640, 0.2813]])} >> Metadata: >> Empty DataFrame >> Columns: [] >> Index: [] b = torch.random(4,3) message = message.append({'x', b}) print(len(message)) >> 6 assert (message[0:2]['x'] == a).all() assert (message[2:6]['x'] == b).all()Internally, the Message stores torch.Tensors in an object called a TensorMessage, which is analogous to a DataFrame. All other types of data are stored inside a DataFrame. You can move data to and from these two formats as well.

message = message.to_dataframe(['x']) # Leave blank to move all tensor columns print(type(message['x'])) >> <class 'pandas.core.series.Series'> message = message.to_tensors(['x']) # Leave blank to move all dataframe columns print(type(message['x'])) >> <class 'torch.Tensor'>You can also move tensors to and from different devices.

message = message.cuda(device_num=0, keys=['x']) # Leave blank to default to device 0 and all tensor columns message = message.cpu(keys=['x']) # Leave blank to default to all tensor columns

Chaining Pipes and Junctions¶

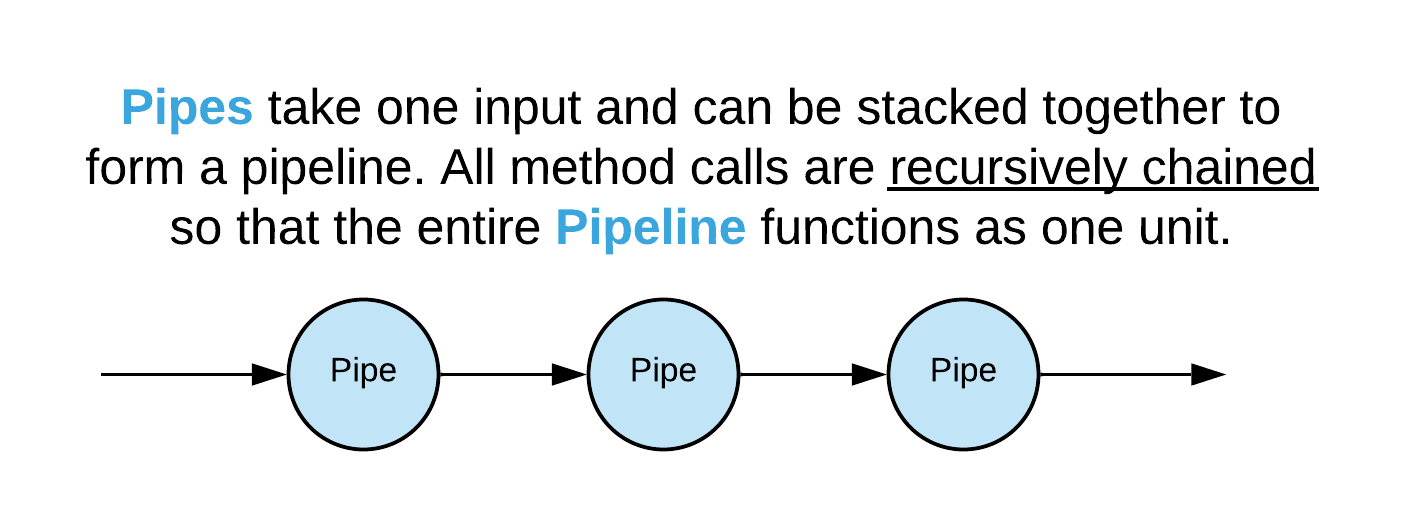

Pipes are meant to represent transformations that can be stacked. This is similar to the approach in functional programming, where individual functions can be chained together to combine their functionality. The methods of a Pipe object are meant to be used in this manner. In particular, the magic methods ‘__getitem__’, ‘__next__’, and ‘__call__’ behave this way for Pipes. Hence, when you call __getitem__ on a pipe (eg. pipe[10]), the pipe will call __getitem__ on its input first before returning. This gives you a functional (in the sense of functional programming) way to chain objects that represent data accessors and/or iterators. This functionality can also be applied to any other method by using the @recursive decorator provided in Fireworks.core.Pipes. Pipes also have another form of recursion: if you call a method/attribute on a Pipe that does not have that method/attribute, it will try to make the call on its input. Hence, you could have a Pipe in the middle of your pipeline that implements some method or has some attribute that a downstream Pipe can use without having to implement it directly.

Let’s look at an example of composing Pipes:

from Fireworks.toolbox.pipes import BatchingPipe, TensorPipe from Fireworks import Message import numpy as np message = Message({"x": np.random.rand(100)}) shuffler = ShufflerPipe(input=message) minibatcher = BatchingPipe(shuffler, batch_size=25) train_set = TensorPipe(minibatcher) for batch in train_set: print(batch)In this example, we start off with some message as the first input. This could alternatively be some Pipe that reads in data from a database, file, etc. As we loop through the last pipe, train_set, the following steps occur at each loop:

- train_set calls for the next element from its input, minibatcher.

- minibatcher calls for the next 25 elements from its input, shuffler. This corresponds to the next batch.

- shuffler return 25 elements from its input, message, to minibatcher. The elements are randomly chosen based on a precomputed shuffle that resets on every full loop through the dataset.

- minibatcher returns the 25 elements to its output, train_set

- train_set converts the columns of its 25 element batch to torch.Tensors and returns the batch. If cuda is installed and enabled, this also moves those tensors to the GPU.

During each step of this process, the elements being returned are Messages. Because of this, the Pipes are decoupled and be re-used and re-composed. Pipes upstream in the pipeline can handle ‘formatting’ tasks such as reading in the data and constructing batches, whereas more downstream pipes can perform preprocessing transformations on those batches, such as normalization, vectorization, and moving data to the GPU. Each successive Pipe adds an additional layer of abstraction, and from the perspective of a downstream Pipe, the input is the only thing that it needs to worry about.

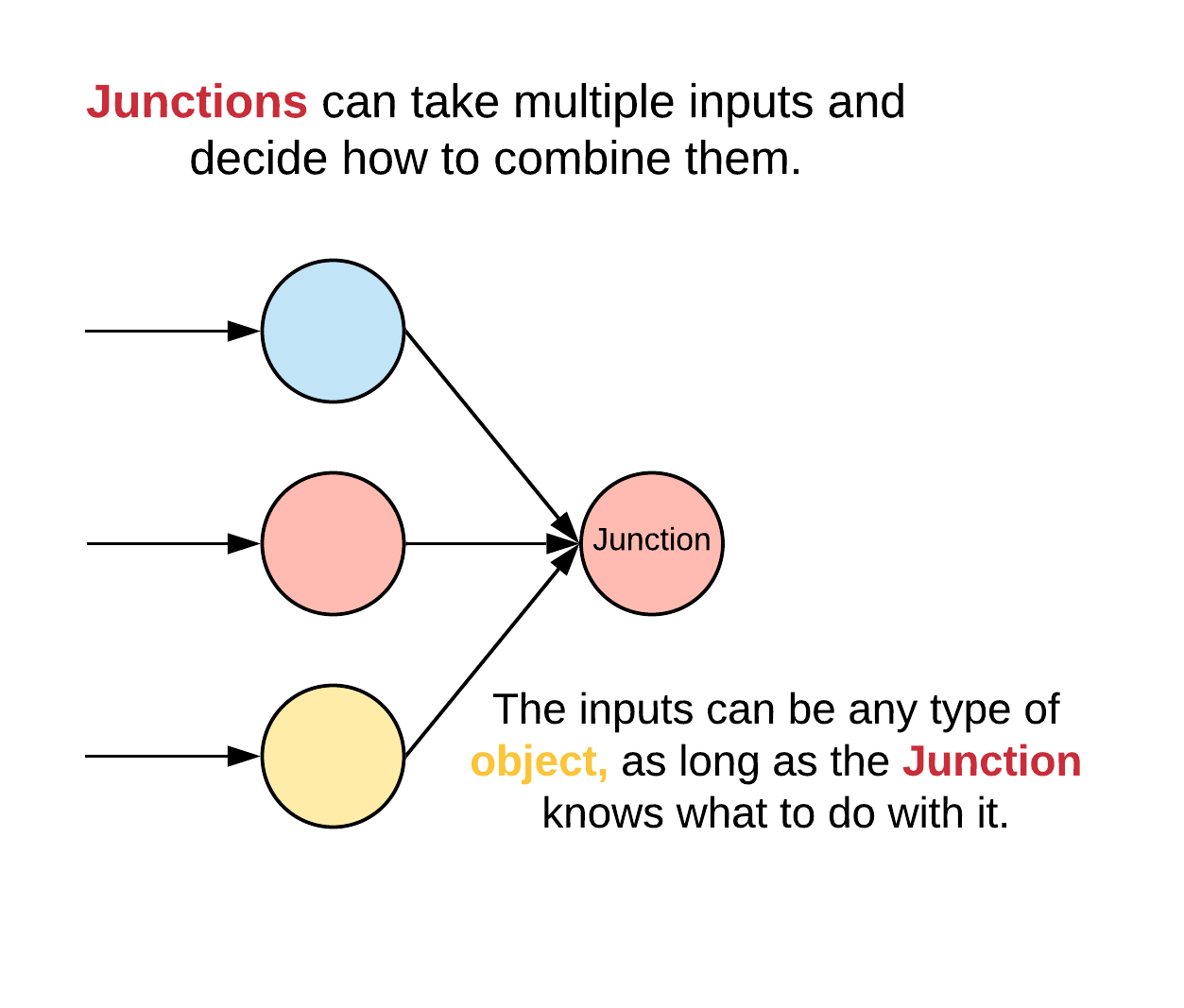

Whereas pipes have a single input, Junctions can have multiple. Having a single input makes recursive method calling well defined; a Pipe can simply refers to its one input. On the other hand, there is ambiguity when doing this for multiple inputs. Should all of the inputs be called or only one? What order should they be called? How should the outputs be combined? Because of this, Pipes have defined methods for recursive method calling which makes it easy to compose them, but Junctions do not. Instead, that logic is implemented on an individual basis depending on what that Junction intends to do.

Lets look at a more involved example involving Junctions:

from Fireworks.toolbox.pipes import LoopingPipe, CachingPipe, ShufflerPipe, BatchingPipe, TensorPipe from Fireworks.toolbox.junctions import RandomHubJunction import numpy as np from Fireworks import Message a = Message({'x': np.random.rand(100)}) b = Message({'x': np.random.rand(200)}) sampler = RandomHubJunction(components={'a':a, 'b':b}) looper = LoopingPipe(sampler) cache = CachingPipe(looper, cache_size=1000) shuffler = ShufflerPipe(cache) minibatcher = BatchingPipe(shuffler, batch_size=30) train_set = TensorPipe(minibatcher) for batch in train_set: print(batch)The RandomHubJunction randomly samples elements from its multiple inputs during iteration. Here, we use this to combine two different data sets (a and b) into a single stream. The RandomHubJunction can only iterate through its inputs in a forward direction; you can’t access items by index (eg. sampled[n]). The LoopingPipe creates the illusion of this functionality by moving the iteration forwards in order to get a requested element. For example, you can call looper[20], and this will return the element that is returned by iterating through sampler 20 times. The CachingPipe stores this information in memory as the name implies. This can be useful for working with extremely large datasets or inputs that are expensive to produce.

Using Databases¶

It’s often useful to use a database query as the starting point for a pipeline, or to write data in the form of a Message into a database. The database module is built on top of SQLalchemy and facilitates this. Let’s say you have a SQL alchemy table (a subclass of declarative_base) which describes your schema and an engine object which can connect to the database. You can create a TablePipe which can query this database as follows:

from Fireworks.extensions.database import TablePipe db = TablePipe(table, engine) query_all = db.query() for row in query_all: print(row) # This will print every column in the table as Messages query_some = db.query(['column_1','column_2']) for row in query_some: print(row) # This will print only 'column_1' and 'column_2'When you use the query method, the object returned is a DBPipe. This can serve as input to a pipeline, as it is iterable. Additionally, you can make your query more precise by applying filters which apply predicates. This lets you make queries of the form “SELECT a FROM b WHERE c” and so on.

filtered = query_some.filter('column_n', 'between', 5,9) # "SELECT column_1, column_2 FROM table WHERE column_n BEWEEN 4 AND 8" filtered.all() # Returns the entire query as a single MessageThe allowed predicates correspond to the allowed filters in SQLalchemy (see https://docs.sqlalchemy.org/en/latest/orm/query.html#the-query-object for more information.) You can also insert Messages into this table, assuming the column names and data types align with the table’s schema. Along with this, you can rollback and commit operations.

db.insert(message) db.rollback() # The insertion will be undone db.insert(message) db.commit() # The transaction will be committed to the db

Model Training¶

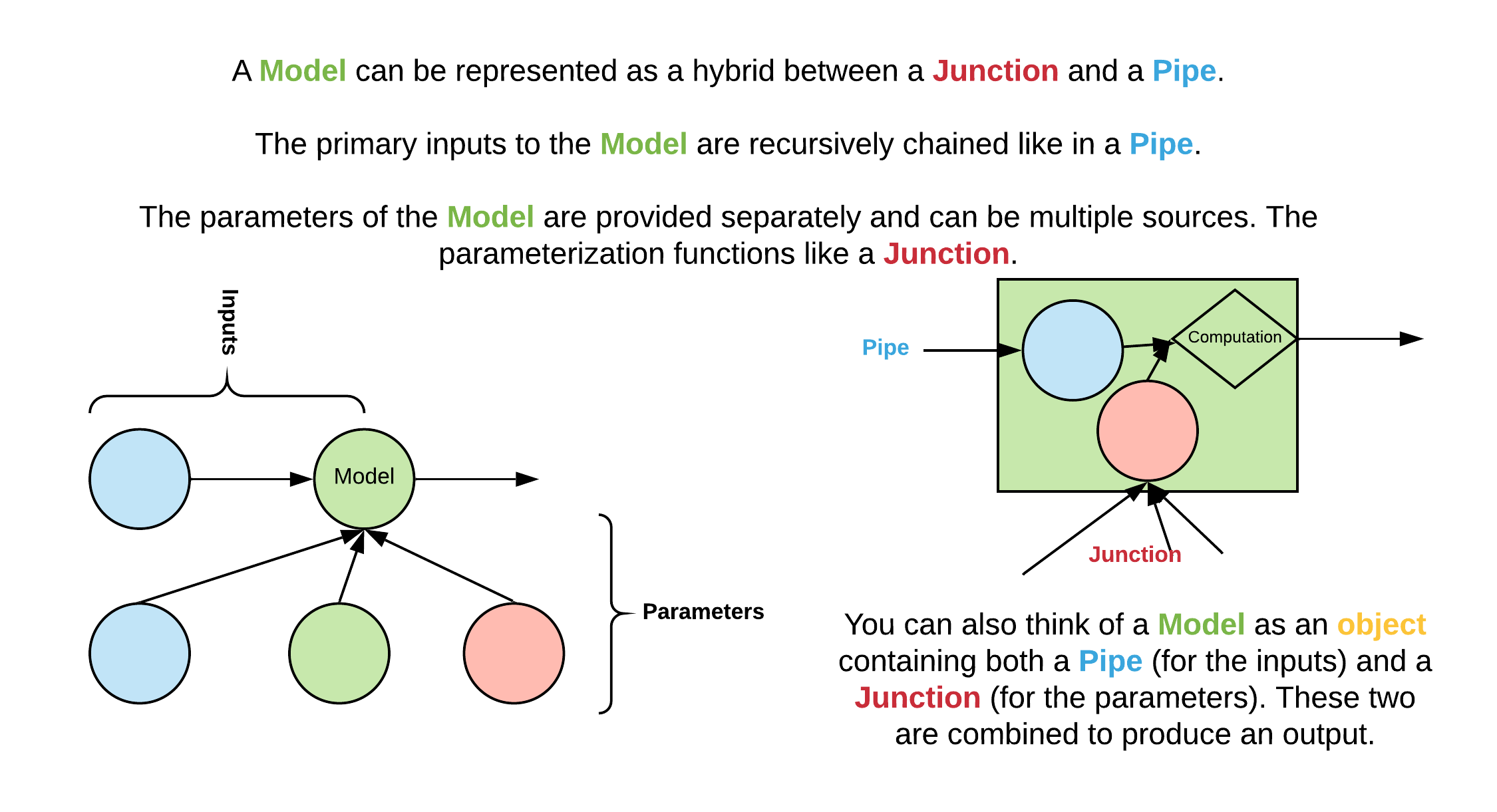

Models function like a hybrid between Pipes and Junctions. They are conceptually like a Pipe in terms of an input/output relationship, but they can be parameterized, and these parameters are represented as components like with a Junction. For example, if we have a model that represents y = m*x+b, the input is x, the output is y, and the parameters are x and b, which are components of the model. This distinction makes it easy to separate out the functional aspect of a model from the stateful aspects.

Let’s look at an example of a Pytorch Model:

import torch from Fireworks import Message, PyTorch_Model class NonlinearModel(PyTorch_Model): required_components = ['a','b', 'c', 'd', 'e'] def init_default_components(self): for letter in ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e']: self.components[letter] = torch.nn.Parameter(torch.Tensor(np.random.normal(0,1,1))) self.in_column = 'x' self.out_column = 'y_pred' def forward(self, message): x = message[self.in_column] message[self.out_column] = (self.a + self.b*x + self.c*x**2 + self.d*x**3 + self.e*x**4) return message my_model = NonlinearModel(components={'a':[1.], 'c': [2.]}) sample_input = Message({'x': torch.rand(10)}) sample_output = my_model(sample_input) print(sample_output['y_pred'])Here, a model is initialized with the parameter ‘a’ set to 1 and ‘c’ set to 2. The other parameters are initialized using the init_default_components method. This method, along with having a ‘required_components’ list is optional, but if defined, the model must have the components specified in ‘required_components’ by the time initialization is complete. Every Model must implement a method called forward() which performs an evaluation on input data. Notice that in this example, the model is evaluated by directly calling it on the argument sample_input. This is the recommended way to invoke a model, because the __call__ method is overridden to first call the Model’s input (if it exists). This lets you compose models by simply placing them in a pipeline. For example, you can do

model_1 = NonlinearModel() model_2 = NonlinearModel(input=model_1) sample_output = model_2(sample_input) # This is equivalent to: same_thing = model_2.forward(model_1.forward(sample_input))Additionally, the __getitem__ and __next__ method’s are overridden in this way, so you can place models in a pipeline and have them apply their forward transformation to data as it is accessed.

model_1.input = train_set # train_set was defined in an earlier example for batch in model_2: print(batch) # This will loop through all batches of train_set and apply model_1.forward, followed by model_2.forwardYou can also enable or disable this functionality:

model_1.disable_evaluation() # model_1 will no longer automatically apply it's forward method when recursively called. sample_output = model_2(sample_input) # This is equivalent to model_2.forward(sample_input) sample_output = next(model_2) # model_1 will still pass through method calls, so that this will return the next batch from train_set, and apply model_2.forward while skipping model_1.forward model_1.enable_evaluation() # Now, model_1 will evaluate when recursively called sample_output = model_2(sample_input) sample_output = next(model_2) # This will apply model_1.forward and model_2.forward on the batch as beforePytorch_Models are also subclasses of PyTorch’s own Module class. This means that you can use them like normal PyTorch Modules and train them using any of the libraries available for training PyTorch models (Ignite, TorchNet, etc.). Fireworks also provides wrappers for the Ignite library for this purpose (see https://github.com/pytorch/ignite for more information).

from Fireworks.extensions import IgniteJunction model = NonlinearModel() base_loss = torch.nn.MSELoss() loss = lambda batch: base_loss(batch['y_pred'], batch['y']) trainer = IgniteJunction(components={'model': model, 'dataset': train_set}, loss=loss, optimizer='Adam', lr=.1) trainer.run(max_epochs=10)As the name implies, IgniteJunction is a Junction that wraps the functionality of an Ignite Engine (the core class in Ignite). We initialize it by providing a model to train along with a training set as components. We also provide a loss function that is evaluated during each iteration on the output of the model. Additional arguments such as the optimizer type to use, learning rate, learning rate schedulers, etc. can be provided as well (see IgniteJunction docs). The IgniteJunction will automatically extract the trainable parameters from the provided model and iterate through the provided training set, computing the loss function and using the chosen optimizer to update the model. You can also manually specify the training closure that is used at each step by providing an option argument ‘update_function’ (see Ignite and Fireworks.extensions.training docs for more details).

If the model being trained has inputs or components that are also models, then their parameters will be updated as well. You can see all of the parameters internally or externally associated with a Model (ie. the parameters that could be involved in model training) by calling the all_parameters() method. You can also control which parameters should be updated by using the freeze() and unfreeze() methods:

model_1 = NonlinearModel() model_2 = NonlinearModel(input=model_1) model_2.all_parameters() # This will list all of the torch.Parameter objects in model_1 and model_2 (model_1.a, model_2.a, etc.) model_1.freeze(['a','d']) # This will prevent model_1.a and model_2.d from updating during training model_2.freeze() # This will freeze all parameters in model_2 during training model_2.unfreeze(['b','c','d']) # This will unfreeze model_2.b, model_2.c, model_2.d during training

State¶

All of the core structures in Fireworks have methods for serializing their state, which makes it straightforward to save and load Pipes, Junctions, and Models. On any of these objects, you can call the get_state() method to get a dictionary-serialized representation of their current state. You can also call set_state() to update this state.

state = model_1.get_state() print(state) model_1.set_state(state)The returned state object consists of two dictionaries, an internal and external. The internal dict is a mapping where the keys are attribute names and the values are serialized attributes that the the object considers part of its state. Pipes have to designate which attributes are considered stateful in their by adding their names to the Pipe.stateful_attributes list. Junctions and objects automatically assign all attributes that don’t begin with ‘__’ to their internal state. The external dict represents variables that an object is using but don’t ‘belong’ to that object. It is a mapping where the values are the names of the object that the attribute belongs to. This provides a method for a model to use parameters from another model without directly copying it. Any updates to that parameter will then be reflected in both models. You could use this to simultaneously train multiple models that are linked together. There is a special syntax for linking parameters in this way:

model_1 = NonlinearModel({'a': [1.], 'b': [0.]}) model_2 = NonlinearModel({'a': (model_2,'a')})In this case, ‘a’ is an external attribute of model_2, and model_2.a is a reference to model_1.a. Any time a component assignment of the form (object, str) is made as in the above example, the Model will assume that this is an external link and treat it as such.

Saving and Loading¶

Fireworks provides utilities for saving data produced by a training run and organizing those files into a single directory. The Experiment class deals with the latter.

from Fireworks.extensions import Experiment description = "Summary of this experiment" my_experiment = Experiment("path_to_experiment_directory", description=description)This will create a folder in the given directory for this experiment and initialize a sqlite file with metadata related to the experiment containing information like the description, time stamp,etc. We can now create file handles and database connections within this directory.

with my_experiment.open('example.txt') as f: f.write('hello') folder_str = my_experiment.open('example2.txt', string_only=True) engine = my_experiment.get_engine('my_engine') # Returns an engine pointing to 'my_engine.sqlite' in the directory connection = my_experiment.get_connection('my_engine') # Returns a connection pointing to 'my_engine.sqlite' and creates engine if it doesn't existThe Experiment.open() method works just like the standard open() function in Python. Additionally, if you set string_only=True, then you can get a string with the path to the location instead.

A scaffold can be used to track multiple objects in a pipeline. You can simultaneously save and load the states of all of the entire pipeline at once, and this way you can record not just model checkpoints, but the state of your preprocessing stages (the random shuffle, current batch, etc.)

from Fireworks import Scaffold message = Message({"x": np.random.rand(100)}) shuffler = ShufflerPipe(input=message) minibatcher = BatchingPipe(shuffler, batch_size=25) train_set = TensorPipe(minibatcher) model = NonlinearModel() my_scaffold = Scaffold({'shuffler': shuffler, 'minibatcher': minibatcher, 'train_set': train_set, 'model': model}) state = scaffold.serialize() # Get a dict with the states of every object tracked by scaffold scaffold.save(path=folder_str, method='json') # Save the state dicts to a json file scaffold.load(folder_str, method='json') # Load the state dicts from a json file into all of the tracked components

Hyperparameter Optimization¶

The Factory class works by repeatedly spawning independent instances of a model, training and evaluating them, and recording computed metrics. These are then used to generate a new set of parameters and repeat the process.

- A factory class takes four arguments:

- Trainer - A function that takes a dictionary of hyperparameters, trains a model and returns the trained model

- Metrics_dict - A dictionary of objects that compute metrics during model training or evaluation.

- Generator - A function that takes the computed metrics and parameters up to this point as arguments and generates a new set of metrics to

use for training. The generator represents the search strategy that you are using. - Eval_dataloader - A dataloader (an iterable that produces minibatches as Message objects) that represents the evaluation dataset.

- Params_table - An SQLalchemy table specifying the schema for storing parameters.

- Metrics_tables - A dict of SQLalchemy tables specifying the schema for storing metrics.

- Engine - An SQLalchemy engine, representing the database connection.

See the model selection example for a demonstration of this process, and the API reference for more details.